Enlarged Prostate (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia)

On this page:

- What is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- How common is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- Who is more likely to have benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- What are the complications of benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- What are the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- What causes benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- How do health care professionals diagnose benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- How do health care professionals treat benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- Can I prevent benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect benign prostatic hyperplasia?

- Clinical Trials for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

What is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a condition in which the prostate gland grows larger than normal, but the growth is not caused by cancer.

The prostate has two main growth phases. The first growth phase happens early in puberty, when the prostate doubles in size. The second growth phase starts around age 25 and continues throughout life.1 BPH often occurs late in the second growth phase.

View full-sized image Your prostate sits below your bladder and surrounds the urethra at the neck of the bladder.

View full-sized image Your prostate sits below your bladder and surrounds the urethra at the neck of the bladder.

Does benign prostatic hyperplasia have another name?

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is also called enlarged prostate, benign prostatic hypertrophy, or benign prostatic obstruction.

How common is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Experts estimate that BPH affects 5% to 6% of men ages 40 to 64 and 29% to 33% of those ages 65 and older.2 BPH is the most common prostate problem in men older than age 50.1 BPH rarely causes symptoms in men younger than age 40.1

Who is more likely to have benign prostatic hyperplasia?

You are more likely to develop BPH if you

- are age 40 and older1

- have a family history of BPH

- have certain conditions such as heart and blood vessel disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, chronic kidney disease, or erectile dysfunction (ED)

- are not physically active

What are the complications of benign prostatic hyperplasia?

An enlarged prostate can cause problems with emptying your bladder. As the prostate grows, it squeezes the urethra. The bladder muscles have to work harder to push urine through the narrowed urethra, which might make your urinary symptoms worse. Eventually, the bladder muscles may weaken and be unable to empty completely, leaving some urine in the bladder. This condition is called urinary retention.

Other complications can include

- blood in your urine, called hematuria

- urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- kidney disease

- bladder stones

What are the symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia?

If you have BPH, you may have

- trouble starting a urine stream or emptying your bladder

- a weak or interrupted urine stream, or dribbling at the end of urination

- nocturia

- urinary urgency

- urinary frequency

- pain during urination

Some medicines can make BPH symptoms worse. Tell a health care professional if you are taking

- over-the-counter cold and cough medicines, such as decongestants or antihistamines

- tranquilizers

- antidepressants

- diuretics

BPH symptoms or difficulty urinating may not be directly related to the size of your prostate. Sometimes, a large prostate may not affect urinating and cause few symptoms. Other times, a slightly enlarged prostate may interfere with urinating and cause more symptoms.

You should discuss any urinary symptoms with a health care professional. Some of these symptoms could be caused by other urinary problems, such as

- bladder problems

- UTIs

- prostatitis

- prostate cancer

Tell a health care professional right away if you

- cannot urinate at all

- feel painful, frequent, and urgent needs to urinate, and have a fever and chills

- have blood in your urine

- feel great discomfort or pain in your lower abdomen or urinary tract

What causes benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Scientists aren’t sure why BPH occurs. They think that factors related to aging may cause BPH because BPH becomes more common with age. Changes in hormone levels as you age may also cause BPH.

How do health care professionals diagnose benign prostatic hyperplasia?

A health care provider diagnoses benign prostatic hyperplasia based on

- a personal and family medical history

- a physical exam

- medical tests

Personal and family medical history

A health care professional may ask

- what symptoms you’re having

- when your symptoms began and how often they occur

- whether you have a history of recurrent UTIs

- what medicines you take, both prescription and over-the-counter

- how much water or other liquids you drink each day and whether you consume caffeine or alcohol

- whether you have had any significant illnesses or surgeries

- whether anyone in your family has had prostate problems

Physical exam

During a physical exam, a health care professional may perform a digital rectal exam to feel your prostate. A health care professional may also check for

- an enlarged bladder

- discharge from your urethra

- enlarged or tender lymph nodes in your groin

Medical tests

You may be referred to a urologist for medical tests. The tests will help diagnose lower urinary tract problems related to BPH. Test results also help health care professionals determine your treatment options. Tests may include

- urinalysis

- prostate tests, such as a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test or prostate biopsy

- urodynamic tests

- cystoscopy

- transrectal ultrasound

A health care professional will review your medical history to help diagnose BPH.

A health care professional will review your medical history to help diagnose BPH.

How do health care professionals treat benign prostatic hyperplasia?

BPH can be treated with watchful waiting, medicines, or surgery. A health care professional will consider how severe your symptoms are and how they affect your quality of life before discussing treatment options with you.

Watchful waiting

If your prostate is slightly enlarged and your symptoms don’t affect your quality of life, a health care professional may recommend watchful waiting, also known as active surveillance. You may still have yearly checkups. Lifestyle changes may also help reduce your symptoms. For example, try to

- drink fewer liquids, particularly before you go out in public or go to bed

- avoid or limit alcohol and caffeine

- be physically active

- empty your bladder completely when you urinate

- use the restroom often and don’t try to hold urine for long periods of time

- avoid or monitor your use of medicines that can make BPH symptoms worse

Medicines

A health care professional may recommend medicines to treat your BPH such as

- alpha blockers, which relax the muscles in the bladder neck and prostate, making it easier to urinate

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), which help stop the growth of or help shrink the prostate, improving your urine flow

- phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, which relax the muscles around the bladder, bladder neck, and prostate and can relieve some symptoms of BPH

Research shows that a combination of an alpha blocker and a 5-ARI may work better than one medicine alone.3

Some medicines may have minor to serious side effects. Tell a health care professional about any side effects you have while taking medicines to treat BPH.

Minimally invasive surgical therapies

Your health care professional may recommend a medical procedure or device to relieve your BPH symptoms. These minimally invasive surgical therapies (MIST) remove enlarged prostate tissue or widen the urethra so urine flows more easily. Examples of MIST procedures and devices include

- transurethral water vapor therapy, which uses water vapor, or steam, to shrink an enlarged prostate

- prostatic urethral lift, which uses tiny implants to lift and hold the prostate away from the urethra so urine can flow more freely

Surgery

You may need surgery to remove part or all of your prostate if

- your medicines do not help

- your symptoms are severe or bother you

- you develop complications

Removing some or all of your prostate can relieve symptoms but may not cure BPH. Surgeons may use different methods to remove part or all of your prostate, including transurethral resection surgery, laser surgery, electrovaporization, or robotic surgery.

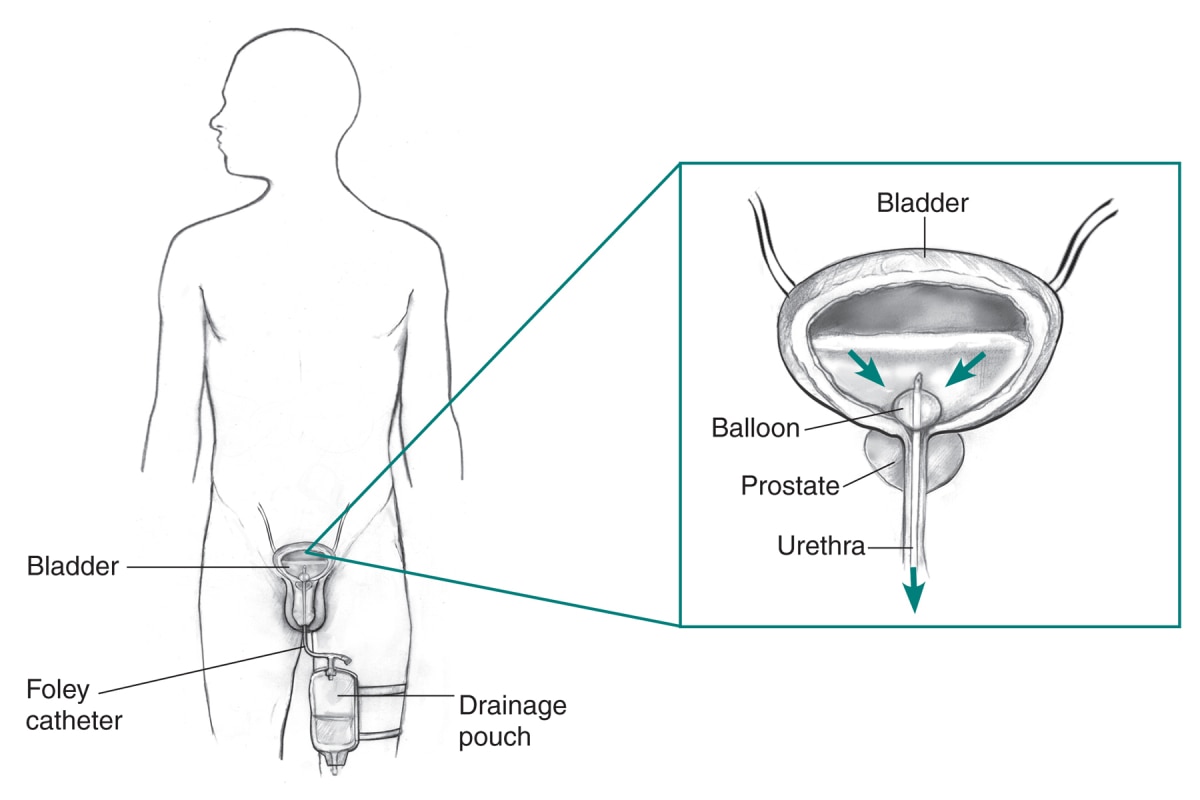

Post-surgery catheter

After surgery, the prostate, urethra, and surrounding areas may be irritated and swollen. You may have trouble urinating. To prevent problems caused by urine staying in the bladder, you may need to use a Foley catheter for several days after surgery. A Foley catheter drains urine from your bladder, through your urethra, and into a pouch attached to your leg.

View full-sized image Foley catheter

View full-sized image Foley catheter

After surgery, you may have painful muscle spasms that squeeze urine out of your bladder. These spasms will eventually stop. Your health care professional may prescribe medicines to relax your bladder muscles and prevent spasms.

Complications of surgery

You may experience complications after BPH surgery, such as

- difficult or painful urination

- temporary urinary incontinence, urgency, or frequency

- blood or blood clots in your urine

- infection

- scar tissue that can form and narrow the urethra or the bladder opening

- sexual problems, including ED, retrograde ejaculation, and infertility

Talk with a health care professional about what to expect after surgery.

Problems that may return after surgery

You may need more treatment if your prostate problems, including BPH, return. In some cases, these problems may return if not enough of the prostate is removed. About 10% of people who had surgery may need more surgery within 20 years.1

A health care professional may recommend a digital rectal exam once a year or more often to check your prostate.

Can I prevent benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Researchers have not found a way to prevent BPH, but being physically active may help reduce your risk. If you have risk factors for BPH, talk with a health care professional about any lower urinary tract symptoms you have and how often you may need a prostate exam. Early treatment can help reduce the effects of BPH on your quality of life.

How do eating, diet, and nutrition affect benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Researchers have not found eating, diet, or nutrition to cause or prevent BPH. However, changes in eating, diet, and nutrition could help treat or lessen some of your symptoms.

You can reduce how often you need to urinate when out in public or while sleeping by limiting how much you drink before outings and bedtime. You can also decrease the number of times you need to urinate by avoiding or reducing alcohol and caffeine intake.

Clinical Trials for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including urologic diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of BPH, such as what causes the prostate to grow larger and how to improve BPH medicines and surgeries.

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for benign prostatic hyperplasia are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on BPH that are federally funded, open, and recruiting at ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe for you. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

NIDDK would like to thank:

Kevin McVary, M.D., Loyola University Medical College